Stefan Dietze invited me to give the keynote presentation at the pre-WWW2015 workshop Linked Learning 2015 in Florence. I’ve already posted a summary of a few of the other presentations I saw, this is a long account (from my speaker’s notes) of what I said. If you prefer you can read the abstract of my talk from the WWW2015 Companion Proceedings or look through my slides & notes on Google. This is a summary of past work at Cetis that lead to our invovement with LRMI, why we got involved, and the current status of LRMI. There’s little here that I haven’t written about before, but I think this is the first time I’ve pulled it all together in this way.

Lorna M. Campbell was co-author for the presentation; the approach I take draws heavily on her presentation from the Cetis conference session on LRMI. Most of the work that we have done on LRMI has been through our affiliation with Cetis. I’ll describe LRMI and what it has achieved presently. In general for this I want to keep things fairly basic. I don’t want to assume a great deal of knowledge about the educational standards or the specifications on which LRMI is based, not so much because I think you don’t know anything, but because, firstly I want to show what LRMI drew on, but also because whenever I talk to people about LRMI it becomes clear that different people have different starting assumptions. I want to try to make sure that we kind of align our assumptions.

LRMI prehistory and precursors

I want to start by reviewing some of what we (Lorna and I and Cetis) did before LRMI and why we got involved in it.

That means talking about metadata. Mostly metadata for the purpose of resource discovery, in order to support the reuse of educational content; we want to support the reuse of educational content in order to justify greater effort going in to the creation of better content and allowing teachers to focus on designing better educational activities. We were never interested in metadata just for its own sake, but, we felt that however good an educational resource is, if you can’t find it you can’t use it.

That means talking about metadata. Mostly metadata for the purpose of resource discovery, in order to support the reuse of educational content; we want to support the reuse of educational content in order to justify greater effort going in to the creation of better content and allowing teachers to focus on designing better educational activities. We were never interested in metadata just for its own sake, but, we felt that however good an educational resource is, if you can’t find it you can’t use it.

And we can start with the LOM, the first international standard for educational technology, designed in the late 1990’s, completed in 2002 (at least the information model was–the XML binding came a couple of years later; other serializations such as RDF were never successfully completed)

And we can start with the LOM, the first international standard for educational technology, designed in the late 1990’s, completed in 2002 (at least the information model was–the XML binding came a couple of years later; other serializations such as RDF were never successfully completed)

We had nothing to do with designing the LOM.

But we did promote its use, for example:

- I worked on a project called FAILTE, a resource discovery service for Engineering learning resources, which involved people with various expertise (librarians, engineering educators, learning technologists) creating what was essentially a catalogue of of LOM records.

- I was also involved in a wider initiative to facilitate similar services across all of UK HE, by creating an application profile for use by joint projects of two organisations, RDN & LTSN (RLLOMAP)

- Meanwhile Lorna was leading work to create an application profile of the LOM with UK-wide applicability (UK-LOM core)

These were fairly typical examples of LOM implementation work at that time. Also, none of them still exists.

All these involve application profiles, that is tailoring the LOM by recommending a subset of elements to use and specifying what controlled vocabularies to use to provide values for them (see metadata principles and practicalities, section IIIA). And there’s a dilemma there, or at least you have to make a compromise, between creating descriptions which make sense in a local setting and meet local needs, and getting interoperability between different implementations of the LOM.

In fact some of the initial LRMI research was a survey of how the LOM is used, looking at LOM records being exposed through OAI-PMH found that most LOM records provided very little beyond what could be provided with simple Dublin Core elements, which agreed with previous work comparing different application profiles (e.g. Goodby, 2004). (See also a similar study by Ochoa et al (2011) conducted at about the same time which focussed repositories that had been designed to use the LOM.)

Anyway, one way or another we got a lot of experience in the LOM and Lorna and I were also part of the team that created the IMS learning resource meta-data specification, especially the IMS Meta-data Best Practice Guide for IEEE 1484.12.1-2002 Standard for Learning Object Metadata, 2006 which is basically a set of guidelines for how to use the LOM.

But I wasn’t talking about the LOM in Florence. Why not? Well, IEEE LOM and IMS Metadata have their uses, and if they work for you that’s great. But I’ve also mentioned some of the problems that we faced when we tried to implement the LOM in more or less open systems: lots of effort to create each record, compromise between interoperability and addressing specific requirements. The structure of the LOM as a single XML tree-like metadata record comprising all the information about a resource does little to help you get around these problems. It also means that the standard as a whole is monolithic: the designers of the LOM had to solve the problems of how to describe IPR, technical, lifecycle issues, and others (then consider that many different resource types can be used as learning resources, and what works a technical description of a text document might not work for an image or video). Solving how to describe educational properties is quite hard enough without throwing solutions to all of these others into the same standard.

So, having learnt a lot from the LOM, we moved on hoping to find approaches to learning resource description that disaggregated the problem (at both design and implementation stages) into smaller less intimidation tasks.

I want to mention some work on Semantic technologies and what was then beginning to be called linked data that Cetis helped commission and were involved in through a working group aournd 2008 – 2009. The Semantic Technologies in Learning and Teaching Jisc mini-project / Cetis working group run by Thanassis Tiropanis et al out of the University of Southampton. The SemTech project aimed to raise the profile of semantic technologies in HE, to highlight what problems they were good at solving. The project included a survey of then-existing semantic tools & services used for education to discover what they were being used for. (they found 36, using a fairly loose definition of “semantic”.

I want to mention some work on Semantic technologies and what was then beginning to be called linked data that Cetis helped commission and were involved in through a working group aournd 2008 – 2009. The Semantic Technologies in Learning and Teaching Jisc mini-project / Cetis working group run by Thanassis Tiropanis et al out of the University of Southampton. The SemTech project aimed to raise the profile of semantic technologies in HE, to highlight what problems they were good at solving. The project included a survey of then-existing semantic tools & services used for education to discover what they were being used for. (they found 36, using a fairly loose definition of “semantic”.

The “five year plan” outlined by that project is worth reflecting on. Basically it suggested that exposing more data which can be used by applications, thus encouraging more data to be released (a sort of optimistic virtuous cycle), and the development of shared ontologies which yield benefits when there you have large amounts of data (Notably, it didn’t suggest spending years locked in a room coming up with the one ontology that would encompass everything before releasing any data).

The development of semantic applications for teaching and learning for HE/FE over the next 5 years could be supported in a number of steps:

- Encouraging the exposure of HE/FE repositories, VLEs, databases and existing Web 2.0 lightweight knowledge models in linked data formats. Enabling the development of learning and teaching applications that make use of linked data across HE/FE institutions; there is significant activity on linked open data to be considered

- Enabling the deployment of semantic-based searching and matching services to enhance learning. Such applications could support group formation and learning resource recommendation based on linked data. The development of ontologies to which linked data will be matched is anticipated. The specification of patterns of semantic tools and services using linked data could be fostered

- Collaborative ontology building and reasoning for pedagogical ends will be more valuable if deployed over a large volume of education related linked data where the value of searching and matching is sufficiently demonstrated. Pedagogy-aware applications making use reasoning to establish learning context and to support argumentation and critical thinking over a large linked data field could be encouraged at this stage.

Semantic technologies in learning & teaching, Final Report, Executive Summary

Our first efforts outside of IEEE LOM were in the Dublin Core Education Application Profile Task Group , between about 2006-2011, attempting to work on a shared ontology. Meanwhile others (notably Mikael Nilsson, KTH Royal Inst Technology, Stockholm) worked to get LOM data in RDF.  This work kind of fizzled out, but we did get an idea of a domain model for learning resources, which rather usefully separated the educationally relevant properties from all the others. The cloud in the middle represents any resource-type specific domain model (say one for describing videos or one for describing textual resources) to which educationally relevant properties can be added. So this diagram represents what I was saying earlier about wanting to disaggregate the problem space so that we can focus on educational matters while other domain experts focus on their specialisms.

This work kind of fizzled out, but we did get an idea of a domain model for learning resources, which rather usefully separated the educationally relevant properties from all the others. The cloud in the middle represents any resource-type specific domain model (say one for describing videos or one for describing textual resources) to which educationally relevant properties can be added. So this diagram represents what I was saying earlier about wanting to disaggregate the problem space so that we can focus on educational matters while other domain experts focus on their specialisms.

I want to mention in passing that around this time (2008/9) work started at ISO/IEC on semantic representation of metadata for learning resources. This was kicked off in response to the IEEE LOM being submitted for ratification as an ISO standard… and it is still ongoing. We’re not involved. Cetis has done no more than comment once or twice on this work.

In fact we did very little metadata work for a while. I thought I was done with it.

At this time there was there was a an idea in educational technology circles that was encapsulated in the term #eduPunk, the idea was that lightweight personal technology could be used to support teaching and learning, a sort DIY approach to learning technology, without the constraints of large institutional, enterprise level systems–WordPress instead of the VLE, folksonomies instead of taxonomies.

In comparison to eduPunk, we were #eduProg. I’ve nothing against the virtuoso wizardry of ProgRock or a technically excellent OWL ontology, and I am not saying there is anything wrong in either. The point I am trying to make is that the interest and attention, the engagement from the Ed Tech community was not in EduProg.

In comparison to eduPunk, we were #eduProg. I’ve nothing against the virtuoso wizardry of ProgRock or a technically excellent OWL ontology, and I am not saying there is anything wrong in either. The point I am trying to make is that the interest and attention, the engagement from the Ed Tech community was not in EduProg.

The attention and engagement was in Open Educational Resources, and we supported a UK HE 3 year, £15Million programme around the release of HE resources under creative commons licences [UKOER]. Cetis provided strategic technical advice and support to the funder and to the 66 projects that released over 10,000 resources. The support include guidelines on technology approaches to the management, description and dissemination of OERs; the guidelines we gave were for lightweight dissemination technologies, minimal metadata, and putting resources where they could be found. We reflected at length on the technology approaches taken by this programme in our book Into the wild – Technology for open educational resources. We recognise the shortcomings in this approach, it’s not perfect, and some people were quite critical of it. If we had been able to point to any discovery services that were based on the LOM or any more directed approach that were unarguably successful we would have recommended it, but it seemed that Google and the open web was at least as successful as any other approach and required less effort on the part of the projects. Partly through UKOER we did see 10,000 resources and more importantly a change in culture so that using social sharing site for education became unremarkable, an I would rather have that than a few 100 perfect metadata descriptions in a repository.

As far as resource description and resource discovery is concerned I think the most important advice we gave was this:

The Learning Resource Metadata Initiative

LRMI launched in 2011. what about it got us back into educational metadata? Let’s start from first principles, and look at the motivation behind LRMI, which is to help people find resources to meet their specific needs. I’ll try to illustrate this.

Meet Pam, a school teacher. Let’s say she wants to teach a lesson about the Declaration of Arbroath.

[See credits, below]

[See credits, below]

What are her specific needs? Well, they relate to her students: their age, their abilities; to her teaching scenario: is she looking for something to use as part of a half hour lesson on a wider topic, or something that will provide a plan of work over a few lessons? introduction or revision? And there is the wider context, she’s unlikely to be teaching about the declaration of Arbroath for its own sake, more likely it will relate to some aspect of a wider curriculum, perhaps history but perhaps also something around civic engagement in Scotland, or relations between Scotland and England, or precursors to the US declaration of independence, but she will be doing so because she is following some shared curriculum or exam syllabus.

She searches Google, finds lots of resources, many of them are no more than the text of the resource.

There are also tea towels and posters.

Those that go further do not necessarily do so in a way that is suitable for her pupils. There’s a Wikipedia article but that’s not really written with school children in mind. Google doesn’t really support narrowing down Pam’s search to match her requirements such as the age and educational level of students, the time required to use in a lesson, the relevance to requirements of national curriculum or exam syllabus, so Pam is forced to look at a series of separate search services based (often) on siloed metadata [examples 1, 2, 3]. It’s worth noting that the examples show categorisation by factors such as Key Stage (i.e. educational level in the English National Curriculum), educational subject, intended educational use (e.g. revision) and others, giving hints as to what Pam might use to filter her search. Google (historically) hasn’t been especially good at this sort of filtering, partly because it cannot always work out the relevance of the text in a document.

What happened to make us think that it was worth addressing this problem was schema.org:

a joint effort, in the spirit of sitemaps.org, to improve the web by creating a structured data markup schema supported by major search engines.

schema.org FAQ

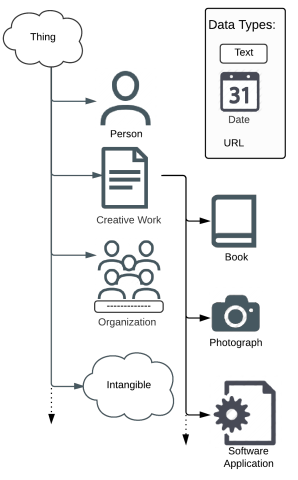

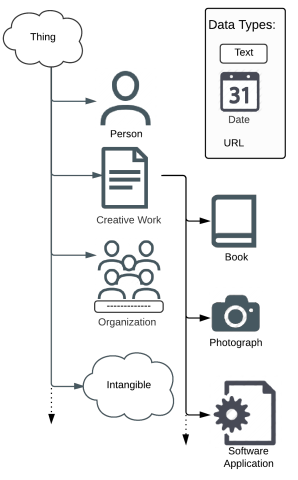

Schema.org provides:

- An agreed hierarchy of entity types (see right).

- An agreed vocabulary for naming the characteristics of resources and the relationships between them.

- Which can be added to HTML (as microdata, RDFa or JSON-LD) to help computers understand what the strings of text mean.

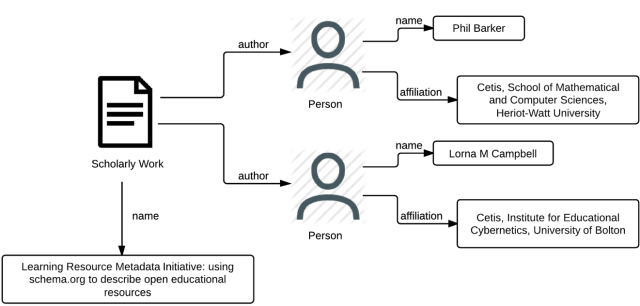

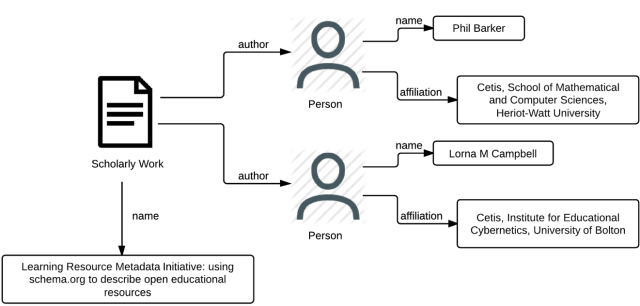

Adding schema.org markup (as microdata) to HTML, turns the code behind a web page from something like:

<h1>Learning Resource Metadata Initiative: using schema.org to describe open educational resources</h1>

<p>by Phil Barker, Cetis, School of Mathematical and Computer Sciences, Heriot-Watt University <br />

Lorna M Campbell, Cetis, Institute for Educational Cybernetics, University of Bolton. April 2014</p>

i.e. just strings, not much to hint as to which string is the authors name, which string is the title of the paper, which string is the author’s affiliation. to something like

<div itemscope itemtype="http://schema.org/ScholarlyArticle">

<h1 itemprop="name">Learning Resource Metadata Initiative: using schema.org to describe open educational resources</h1>

<p itemprop="author" itemscope itemtype="http://schema.org/Person">

<span itemprop="name">Phil Barker</span>,

<span itemprop="affiliation">Cetis, School of Mathematical and Computer Sciences, Heriot-Watt University</span></p>

<p itemprop="author" itemscope itemtype="http://schema.org/Person">

<span itemprop="name">Lorna M Campbell</span>,

<span itemprop="affiliation">Cetis, Institute for Educational Cybernetics, University of Bolton</span></p>

</div>

where the main entities and their relationships are marked and text that related to properties of those items is identified: a Scholarly Article is related to two Persons who are the authors; some of the text is the name of the Scholarly Article (i.e. its title), the names of the Persons and their affiliations. Represented graphically, we could show this information as:

An entity – relation graph identifying the types of entities, their relationships to each other and to the strings that describe significant properties.

At this point the LRMI was initiated, a 3 year project funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation (and later wth some additional funding from the Hewlett Foundation), managed jointly by one organisation committed to open education (Creative Commons) and another (AEP) from the commercial publishing world, with input from education,publishers and metadata experts.

I was on the technical working group. We issued a call for participation; gathered use cases; and did the usual meeting and discussing to hammer out how to meet those use cases. We worked more or less in the open,–there was an invitation only face to face meeting near the beginning (limited funding so couldn’t invite everyone) after that all the work was on open email discussion lists and conference calls. Basing the work on schema.org allowed us to leave all the generic and resource-format specific stuff for other people to handle, and we could focus just on the educational properties that we needed.

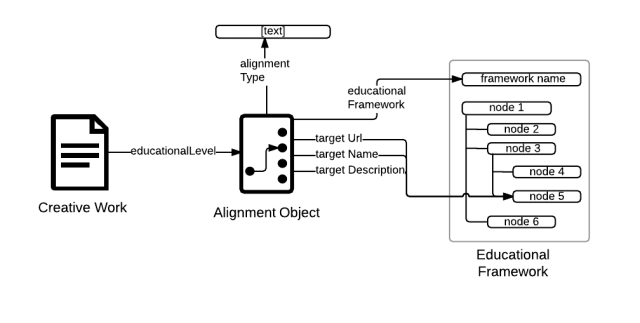

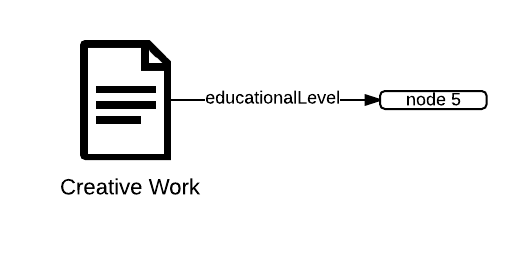

The slide on the left shows what came out. The first two properties are major relationships to other entities, and alignment to some educational framework and the intended audience, the others are mostly simple characteristics. All are defined in the LRMI specification. In a previous blog post I have attempted further explanation of the Alignment Object. Most of these were added to Schema.org in 2013, the link to licence information was added later.

Current state of LRMI and future plans.

LRMI has been implemented by a number of organisations, some with project funding to encourage uptake, others more organically. One of the nice things about piggy-backing on schema.org is that people who have never heard of LRMI are using it.

Not every organisation on this list exposes LRMI metadata in its webpages, some harvest it or create it and use it internally. The Learning Registry is especially interesting as it is a data store of information about learning resources in many different schema, which uses LRMI as JSON-LD for (many of its) descriptive records. We have reported in some depth on the various ways in which LRMI has been implemented by those projects who are funded through the initiative.

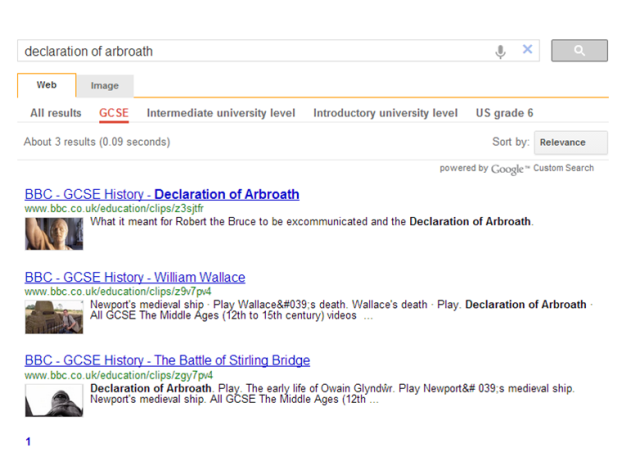

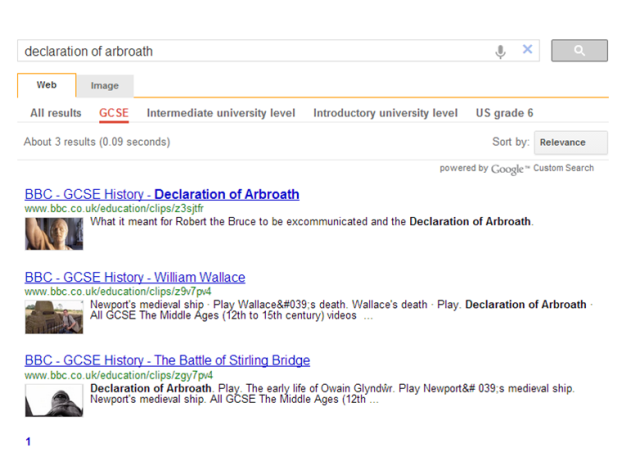

We can create a Google custom search engine that looks for the alignment object–this in itself is a good indicator that someone has considered the resource to be useful for learning; and we can add filters to find learning resources useful for specific contexts, in this case different educational levels.  This helps Pam narrow down her search–at least in a proof of concept way, as they stand these are not intended to be useful services.

This helps Pam narrow down her search–at least in a proof of concept way, as they stand these are not intended to be useful services.

I would like to note the following points from these implementations:

- they exist. That’s a good first step.

- not every implementation exposes LRMI metadata, some use it internally.

- schema.org is a lightweight, loose ontology, implementation is looser.

The people implementing it tend to make mistakes. Expect to find strings where there should be a link and also find links and properties where they shouldn’t be. (see also Martin Hepp’s presentation from Ontologies to Web Ontologies and the Bulletin of the Association for Information Science and Technology Vol. 41 No 4, “the charm of weak semantics”)

- there is no agreement on value spaces, either terms or meanings (e.g. educational level, 1st Grade, Primary 1).

The Gates funding for LRMI is now complete, and as an organization LRMI is now a task group of the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. That provides us with with the mechanisms and governance required to maintain, promote, and if necessary extend the specification. It does not mean that LRMI terms are DC terms, they’re not, they’re in a different namespace. DCMI is more than a set of RDF terms, it’s a community of experts working together, and that’s what LRMI is part of. The LRMI specification is now a community specification of DCMI, conforming to the the requirements of DCMI, such as having well-maintained definitions in RDF, which align with the schema.org definitions but are independently extensible.

The Gates funding for LRMI is now complete, and as an organization LRMI is now a task group of the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. That provides us with with the mechanisms and governance required to maintain, promote, and if necessary extend the specification. It does not mean that LRMI terms are DC terms, they’re not, they’re in a different namespace. DCMI is more than a set of RDF terms, it’s a community of experts working together, and that’s what LRMI is part of. The LRMI specification is now a community specification of DCMI, conforming to the the requirements of DCMI, such as having well-maintained definitions in RDF, which align with the schema.org definitions but are independently extensible.

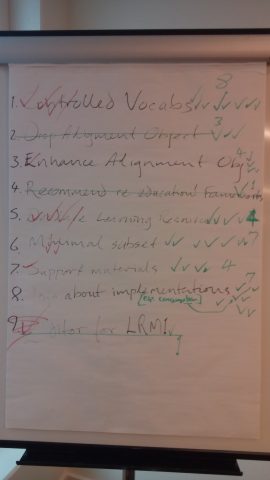

The planned work of task group is shown on the group wiki, and includes:

- Extending LRMI: Events? Courses?

- contributing via new schema.org extension mechanism?

- Recommended value vocabularies

- Linked data representation of educational frameworks (alignment)

(There’s also a background interest in the use of LRMI beyond the original schema.org scenario, for example as stand-alone JSON-LD or as EPUB metadata for eTextBooks)

It’s customary to allow time for the audience to ask difficult questions of the presenter. I tried to forestall that by asking the audience’s opinion on these questions:

- Does this help with the endeavour to expose lightweight linked data?

- (can you get the data out of web pages?)

- How do we encourage linked data representation of educational frameworks?

- How much goes into schema.org (or similar) or should we just reuse existing ontologies?

- Can you cope with the the quality of data that can be provided at web-scale?

Reflections on the presentation

As far as I could judge from the questions that I couldn’t answer well, the weak points in the presentation, or in LRMI may be, seem to be around gauging the level of uptake: how many pages are there out there with LRMI data on them? I don’t know. The schema.org pages for each entity show usage , for example the Alignment Object is on between 10 and 100 domains, but I do not know the size of those domains. That also misses those services that use LRMI and do not expose it in their webpages but would expose it as linked data in some other format. I suspect uptake is less than I would like, and I would like to see more.

As presenter I was happy that even after I had talked about all that for about 45 minutes, there were people who wanted to ask me questions (the forestalling tactic didn’t work), and even after that there were people who wanted to talk to me instead of going for coffee. That seems to be a good indicator that there was interest from the workshop’s audience.

Image credits: Photo of Pam Robertson, teacher, by Vgrigas (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 ], via Wikimedia Commons; reproduction of Tyninghame (1320 A.D) copy of the Declaration of Arbroath, 1320, via Wikimedia Commons. Logos (Heriot-Watt, Cetis, LRMI, Semtech etc.) are property of the respective organisation. Unless noted otherwise on slide image, other images created by the authors and licensed as CC-BY.